People disagree. Most genuine disagreement stems, I believe, from different people valuing different things, or valuing the same things differently. Every single one of us has a different view of the world, and that’s a good thing! Life would be boring if we all felt the same way about things, and most of human progress develops from rivalry, disagreement, the synthesis of differing perspectives. But sometimes, if we’re not careful, things can get ugly:

The web is turning writing into a conversation. Twenty years ago, writers wrote and readers read. The web lets readers respond, and increasingly they do—in comment threads, on forums, and in their own blog posts.

Many who respond to something disagree with it. That’s to be expected. Agreeing tends to motivate people less than disagreeing. And when you agree there’s less to say. You could expand on something the author said, but he has probably already explored the most interesting implications. When you disagree you’re entering territory he may not have explored.

The result is there’s a lot more disagreeing going on, especially measured by the word. That doesn’t mean people are getting angrier. The structural change in the way we communicate is enough to account for it. But though it’s not anger that’s driving the increase in disagreement, there’s a danger that the increase in disagreement will make people angrier. Particularly online, where it’s easy to say things you’d never say face to face.

If we’re all going to be disagreeing more, we should be careful to do it well.

– Paul Graham, How To Disagree

I think Paul Graham unearthed certain interesting ideas about human nature that we have yet to transcend, perhaps vestigial habits that were once completely rational but are now rather obsolete in our new and rapidly changing environments.

For the most part, disagreements are best resolved through civil discourse. I say “best” with regards to the interests of all parties involved. The “best” short term response for a single individual may be to crush his enemies totally, as famously advised by Machiavelli:

“For it must be noted, that men must either be caressed or else annihilated; they will revenge themselves for small injuries, but cannot do so for great ones; the injury therefore that we do to a man must be such that we need not fear his revenge.”

Annihilation, thankfully, is rarely an option these days. The Cold War did not escalate past what it did because of the threat of Mutually Assured Destruction. Most human relations are inextricably intertwined these days, and it is exceedingly rare that we have an opportunity to attack someone where we do not indirectly harm ourselves.

1: Ask Questions. People often develop emotional bonds to their own ideas and perspectives, and get offended when people attack them. Socrates had the right idea– instead of attacking or insulting a person’s ideas (and by extension, whether you mean to or not, the person himself), ask questions.

This has multiple positive effects- it creates the impression that you’re trying to understand the person’s perspective, which is non-threatening. and makes you look good. By feigning ignorance, you make it their responsibility to clarify and explain their ideas, and diminish the odds that you might accidentally say something stupid or offensive. If they’re right, you have the option of acknowledging it in a civil and respectful manner. If they’re wrong, it allows them the opportunity to backpedal and correct themselves. If they respond negatively at any point, your hands are clean. “When you surround an army, leave an outlet free.” – Sun Tzu

2: Don’t take things personally. We are all guilty of taking things far more personally than we ought to, myself included. Every now and then I get comments on my blog or Facebook that I instinctively perceive as personal attacks- some of them are, and some of them aren’t. The best way of dealing with them, as far as I know, is to begin by thanking the person for their response– after all, that they attempted to correspond with us at all is something that we ought to cherish- the vast majority of people in the world are completely indifferent to anything we say. Critics, dissidents and haters are opportunities for us to demonstrate grace and magnanimity. Dealing with them respectfully often disarms them, and some of them will become valuable allies and supporters.

3: Find something you can both agree on. This is my favourite tactic. There is almost always something that people can agree about in the midst of any agreement. Make an effort to find such common ground, and you communicate that you’re trying to learn, understand and grow- you’re not interested in attacking the other person for the sake of it. By getting the other person involved in building something together, you subtly get them to see you as something more complex and potentially valuable than a hateful antagonist, and this added dynamic will prove useful in future interactions.

4: Acknowledge your mistakes. Nobody gets it right all the time. By acknowledging your mistakes, you communicate that you’re a reasonable person, and reasonable people generally like dealing with other reasonable people. Simple enough. It’s important to be sincere and succinct. Try not to explain yourself too much (I am often guilty of this) or weasel your way out of taking responsibility for your mistake, because it often gets misinterpreted as insincerity. Take responsibility.

4: Play nice. Being an asshole can be fun, but it is often self-defeating. It never hurts to be civil and respectful. We tend to remember how we felt about something much better than what was discussed, and it’s best to leave a good impression. The world is quickly becoming a smaller place at an exponential rate. Keep your hands clean, and work on winning the hearts and minds of others. Don’t be sarcastic or condescending. Aim to win your opponent over, as well as everyone else who may be watching. Turn on the charm. A Hero never overlooks an opportunity to invest in a potential ally.

5: Walk away. Some people are just impossible, and not worth the effort. They may respond to your questions with personal attacks, and refuse to find common ground. It’s often hard to resist taking a potshot at such people. No action or interaction goes unobserved. Grace under fire is an admirable trait, and you can earn the admiration of people that you care about by when dealing gracefully with unreasonable people. Also, walking away always looks so badass in the movies. A Hero chooses his battles wisely.

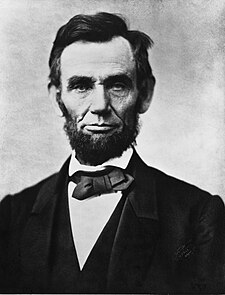

Abraham Lincoln clearly had it well figured out when he said, “Do I not destroy my enemies when I make them my friends?”

Like a boss.

lol there are 6 steps